Share…

How to Use

Each title is followed by links to download the e-Book.

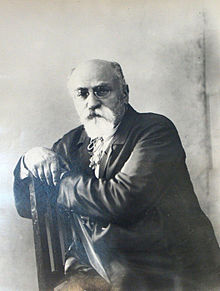

German philosopher, political economist, historian, sociologist, humanist, political theorist, and revolutionary cred ited as the founder of communism. Marx summarized his approach to history and politics in the opening line of the first chapter of The Communist Manifesto [1848]: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” Marx argued that capitalism, like previous socioeconomic systems, will produce internal tensions which will lead to its destruction. Just as capitalism replaced feudalism, socialismwill in its turn replace capitalism and lead to a stateless, classless society which will emerge after a transitional period, the “dictatorship of the proletariat”.

ited as the founder of communism. Marx summarized his approach to history and politics in the opening line of the first chapter of The Communist Manifesto [1848]: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” Marx argued that capitalism, like previous socioeconomic systems, will produce internal tensions which will lead to its destruction. Just as capitalism replaced feudalism, socialismwill in its turn replace capitalism and lead to a stateless, classless society which will emerge after a transitional period, the “dictatorship of the proletariat”.

While Marx remained a relatively obscure figure in his own lifetime, his ideas began to exert a major influence on workers’ movements shortly after his death. This influence gained added impetus with the victory of the Marxist Bolsheviks in the Russian October Revolution in 1917, and few parts of the world remained significantly untouched by Marxian ideas in the course of the twentieth century.

Frie drich Engels, an illustrious German philosopher, was born on November 28, 1820 in Barmen, Rhine province, Prussia. His father was an affluent businessman, who owned a textile factory and was also a partner in a cotton plant in Manchester, England. Engels and his father had very different plans for his career, Engels began to exhibit radical philosophies from a very young age while his father was adamant to carve out a career in commerce for him. The two often sparred on this issue, and Engels was just as unyielding as his father. He did not complete his secondary education, and began publishing articles on philosophy and economics under the pseudonym of Friedrich Oswald. Meanwhile, in 1838, he also appeased his father by working at an export firm, due to which Engels could not benefit from a university education. Engels voluntarily served in an artillery regiment for a year, and was applauded for his military prowess. Upon settling in Berlin, Engels discovered the works banned authors such as Ludwig Borne, Karl Gutzkow, Heinrich Heine and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, of which Hegel influenced him the most and he openly embraced the Hegelian society. Along with Bruno Bauer and Max Stirner, he joined the ‘Young Hegelians’ society and accepted the Hegelian dialect. The society converted an agnostic Engels into an atheist militant, this conversion was made easy by his radical inclinations against the foundations of Christianity and repressive social notions.

drich Engels, an illustrious German philosopher, was born on November 28, 1820 in Barmen, Rhine province, Prussia. His father was an affluent businessman, who owned a textile factory and was also a partner in a cotton plant in Manchester, England. Engels and his father had very different plans for his career, Engels began to exhibit radical philosophies from a very young age while his father was adamant to carve out a career in commerce for him. The two often sparred on this issue, and Engels was just as unyielding as his father. He did not complete his secondary education, and began publishing articles on philosophy and economics under the pseudonym of Friedrich Oswald. Meanwhile, in 1838, he also appeased his father by working at an export firm, due to which Engels could not benefit from a university education. Engels voluntarily served in an artillery regiment for a year, and was applauded for his military prowess. Upon settling in Berlin, Engels discovered the works banned authors such as Ludwig Borne, Karl Gutzkow, Heinrich Heine and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, of which Hegel influenced him the most and he openly embraced the Hegelian society. Along with Bruno Bauer and Max Stirner, he joined the ‘Young Hegelians’ society and accepted the Hegelian dialect. The society converted an agnostic Engels into an atheist militant, this conversion was made easy by his radical inclinations against the foundations of Christianity and repressive social notions.

In 1843, Engels encountered Moses Hess, who convinced him to believe that communism is the only logical solution to progress, and advised him to go to England, where class differences were becoming more and more prominent. Engels cajoled his father into sending him to work at his textile plant in Manchester, to which his father happily agreed. In England, Engels made remarkable progress at work and used his free time to read and compose articles on economic and political scenarios. He began researching on issues such as child labor and the lives and conditions of the workers. His articles began to get acclaim upon being published in magazines such as ‘The Northern Star’, ‘New Moral World’ and the ‘Democratic Review’, and he became an enthusiastic supporter of English labor and Chartist movements. In 1844, he decided to return to Germany, and during his journey, he met Karl Marx in Paris, an encounter that would lead to a lifelong friendship. Engels assisted Marx in writing a critic on the ‘Young Hegelians’ which would be published as ‘The Holy Family’. In 1845, Engels published ‘The Conditions of the Working Class’.

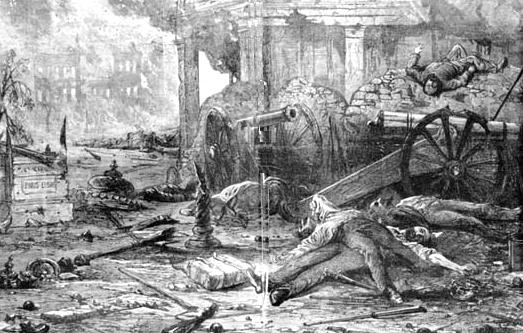

In 1845, Engels went to Brussels to join Marx in organizing the German workers like the French and English workers were uniting. They became members of the German Communist League, and were asked to draft a manifesto for the organization, which is now widely known as the Communist Manifesto. In 1848, Marx and Engels began openly participating in the revolution that had spread to Prussia from France. They settled in Cologne, and began editing a paper, Neue Rheinische Zeitung, that spread their revolutionary notions advocating that a democracy would be the first step towards communism. However, in 1849, the Prussian government shut down the paper and revoked Marx’s Prussian citizenship. Engels did not leave Prussia for some time, and organized an uprising in South Germany, but upon its failure he fled to England and reunited with Marx.

Back in England, Marx and Engels began reconstructing the Communist League. Funds began to get scarce, and while Marx was busy working on Das Kapital, Engels decided to go back to work at his father’s textile plant in Manchester. In 1864, he was made a partner at the plant due to his impressive and productive work record. Engels kept in touch with Marx throughout his life, and also supported him financially until Marx’s death. He assisted Marx in editing a few articles as Marx regarded him as highly informed on economics, political and military issues. In 1896, these articles were published under Engels’ name as the ‘Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany in 1848’. The same year, Engels sold off his share in the plant and moved to London to work with Marx. They worked together till Marx’s death in 1883.

After Marx’s death, Engels struggled to keep the spirit of communism alive, and gained the status of the first Marxist. He held regular correspondence with the German Social Democrats and other followers all over Europe. He also undertook the task of compiling the second and third volumes of Das Kapital, using Marx’s extensive research to assist him. Engels made several notable contributions to the field of political and economic philosophy, including highly acclaimed works such as ‘The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State’ and ‘Ludwig Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy’. Friedrich Engels died on August 5, 1895, after a prolonged battle with throat cancer.

One of the leaders of the Bolshevik party since its formation in 1903. Led the Soviets to power in October, 1917. Elected to the head of the Soviet government until 1922, when he retired due to ill health.

Lenin, born in 1870, was committed to revolutionary struggle from an early age – his elder brother was hanged for the attempted assassination of Czar Alexander III. In 1891 Lenin passed his Law exam with high honors, whereupon he took to representing the poorest peasantry in Samara. After moving to St. Petersburg in 1893, Lenin’s experience with the oppression of the peasantry in Russia, coupled with the revolutionary teachings of G V Plekhanov, guided Lenin to meet with revolutionary groups. In April 1895, his comrades helped send Lenin abroad to get up to speed with the revolutionary movement in Europe, and in particular, to meet the Emancipation of Labour Group, of which Plekhanov head. After five months abroad, traveling from Switzerland to France to Germany, working at libraries and newspapers to make his way, Lenin returned to Russia, carrying a brief case with a false bottom, full of Marxist literature.

Lenin, born in 1870, was committed to revolutionary struggle from an early age – his elder brother was hanged for the attempted assassination of Czar Alexander III. In 1891 Lenin passed his Law exam with high honors, whereupon he took to representing the poorest peasantry in Samara. After moving to St. Petersburg in 1893, Lenin’s experience with the oppression of the peasantry in Russia, coupled with the revolutionary teachings of G V Plekhanov, guided Lenin to meet with revolutionary groups. In April 1895, his comrades helped send Lenin abroad to get up to speed with the revolutionary movement in Europe, and in particular, to meet the Emancipation of Labour Group, of which Plekhanov head. After five months abroad, traveling from Switzerland to France to Germany, working at libraries and newspapers to make his way, Lenin returned to Russia, carrying a brief case with a false bottom, full of Marxist literature.

On returning to Russia, Lenin and Martov created the League for the Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, uniting the Marxist circles in Petrograd at the time. The group supported strikes and union activity, distributed Marxist literature, and taught in workers education groups. In St. Petersburg Lenin begins a relationship with Nadezhda Krupskaya. In the night of December 8, 1895, Lenin and the members of the party are arrested; Lenin sentenced to 15 months in prison. By 1897, when the prison sentence expired, the autocracy appended an additional three year sentence, due to Lenin’s continual writing and organising while in prison. Lenin is exiled to the village of Shushenskoye, in Siberia, where he becomes a leading member of the peasant community. Krupskaya is soon also sent into exile for revolutionary activities, and together they work on party organising, the monumental work: The Development of Capitalism in Russia, and the translating of Sidney and Beatrice Webb‘s Industrial Democracy.

After his term of exile ends, Lenin emigrates to Münich, and is soon joined by Krupskaya. Lenin creates Iskra, in efforts to bring together the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, which had been scattered after the police persecution of the first congress of the party in 1898.

Lenin – Entry submitted by Leon Trotsky

Lenin and the Bourgeois Press – Boris Baluyev

The Life and Work of V. I. Lenin

Paul Lafargue was born in 1842 in Santiago, Cuba of mixed heritage. He moved with his family to France as a young boy where he studied medicine and first became involved in politics as a follower of Proudhon. It was while a representative of the French working class movement to the First International he became friendly with Marx and Engels and changed his views to those of Marx. Married in 1868 to Laura Marx, Marx’s second daughter, the Lafargue’s began several decades of political work together, financially supported by Engels.

Paul was one of the founders of the Marxist wing of the French Workers Party. From 1861 took part in the republican movement. In 1870-71 he carried on organisational and agitational work in Paris and Bordeaux; after the fall of the Commune he fled to Spain where he fought for the line of the General Council; they then settled in London. After the bloody May Day in Fourmis (1891) he was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment. Lafargue fought against reformism and Millerandism and was an advocate of women’s rights.

Paul was one of the founders of the Marxist wing of the French Workers Party. From 1861 took part in the republican movement. In 1870-71 he carried on organisational and agitational work in Paris and Bordeaux; after the fall of the Commune he fled to Spain where he fought for the line of the General Council; they then settled in London. After the bloody May Day in Fourmis (1891) he was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment. Lafargue fought against reformism and Millerandism and was an advocate of women’s rights.

Lafargue was an influential speaker and wrote numerous works on revolutionary Marxism, including the humorous and well-known, “The Right to Be Lazy” and “Evolution and Property”. By age 70, in 1911, the elderly couple commit suicide together, having decided they had nothing left to give to the movement to which they devoted their lives.

Rosa Luxemburg was a Polish political philosopher, economist, marxist, and revolutionary who played a pivotal role during the First World War and the German Revolution. She founded, along with Karl Liebnecht, the anti-war Spartacus League in 1915, which later became the Communist Part of Germany. The Red Flag, the vital organ of the Spartacist movement, was also founded by her during the German Revolution.

Until the Russian Revolution, Luxemburg believed that a revolution would certainly take place in Germany, but when Russia revolutionized, it became one of the most important experiences in Luxemburg’s life. She moved to Warsaw to participate, and was captured. She gained valuable ideas from this experience which she presented in her 1906 work The Mass Strike. According to Luxemburg, mass strikes are the best method the working class can use to gain victory. Mass strikes are likely to act as a fuel in any socialist revolution. Her point of view differed from Lenin’s as she did not believe in a tightly-structured political party. Through the Dialectic of Spontaneity and Organization, her significant political philosophy, Luxemburg put forward the idea that through spontaneity, organization and order can be achieved, when working for class-struggle through a political party. She held the view that class struggle reaches a higher level when it starts spontaneously from within the proletarians.

In her 1913 work, The Accumulation of Capital, Luxemburg analyzed economics and politics and put forward the theory that the spread of capitalism in undeveloped areas of the world leads to the nuisance of imperialism. She also left the Social Democratic Party during this time as she struggled for the initiation of mass action.

Along with Karl Liebknecht, she founded the Spartacus League, which was based on her 1916 pamphlet, The Crisis in the German Social Democracy, written in jail. Through the League, they intended to end the World War and establish the rule of the working class, but the actual impact of the League during the war did not prove to be as strong as it was intended.

Written in 1922, The Russian Revolution criticized the Lenin’s party for their terror-inducing and tyrannical methodologies. Luxemburg championed democracy, unlike Lenin who supported democratic centralism. She also chastised the Bolsheviks’ opportunist and agrarian political policies during The Russian Revolution.

Due to her strong opinions and ideas during the Spartacus Revolt, she was arrested in Berlin by conservative paramilitary forces known as the Free Corps, and was later murdered in January 1919.

Her collection of political philosophies, collectively called Luxemburgism, is a revolutionary set of ideas under the realm of Marxism. The significant ideas of Luxemburgism include a pledge to struggle for democracy and the spontaneous class struggle which would organize itself to bring about revolution.

Many socialists and Marxists may disagree with the philosophy of Rosa Luxemburg, but she will always remain as a steadfast revolutionary thinker who sacrificed her life for her principles. Her commitment to democracy and strong negation of capitalism has earned her the respect of Socialists from around the globe. The commemoration of Rosa Luxemburg as a martyr of Socialism takes place to this day, among the left-wing politicians of Germany, irrespective of their identification and agreement to her political philosophy. Decades after her murder, she is alive in her revolutionary ideas.

Hegel was born in Stuttgart on August 27, 1770, the son of Georg Ludwig Hegel, a revenue officer with the Duchy of Wurttemburg. Eldest of three children (his younger brother, Georg Ludwig, died young as an officer with Napoleon during the Russian campaign), he was brought up in an atmosphere of Pattached to his sister, Christiane, who later developed a manic jealousy of Hegel’s wife when he married at age 40 rotestant pietism. His mother was teaching him Latin before he began school, but died when he was 11. He was very and committed suicide three months after his death. Hegel was deeply concerned by his sister’s psychosis and developed ideas of psychiatry based on concepts of dialectics.

of Pattached to his sister, Christiane, who later developed a manic jealousy of Hegel’s wife when he married at age 40 rotestant pietism. His mother was teaching him Latin before he began school, but died when he was 11. He was very and committed suicide three months after his death. Hegel was deeply concerned by his sister’s psychosis and developed ideas of psychiatry based on concepts of dialectics.

Hegel soon became thoroughly acquainted with the Greek and Roman classics while studying at the Stuttgart Gymnasium (preparatory school) and was familiar with German literature and science. Encouraged by his father to become a clergyman, Hegel entered the seminary at the University of Tübingen in 1788. There he developed friendships with the poet Friedrich Hölderlin and the philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling. From Hölderlin in particular, Hegel developed a profound interest in Greek literature and philosophy. Early on and throughout his life, Hegel recorded and committed to memory everything he read – and he read profusely! Hegel worshipped Goethe and long regarded himself as inferior to his brilliant contemporaries Schelling and Hölderlin.

The Germany of Hegel’s time was extremely backward from an economic point of view. Germany was a myriad of tiny, backward states, relatively insulated from the turmoils of Europe. He was an avid reader of Schiller and Rousseau. Hegel was 18 when the Bastille was stormed and the Republic declared in France and Hegel was an enthusiastic supporter of the Revolution, and participated in a support group formed in Tübingen. Hegel finished his first great work, The Phenomenology of Mind on the very eve of the decisive Battle of Jena, in which Napoleon broke the Prussian armies and dismembered the kingdom. French soldiers entered Hegel’s house and set it afire just after he stuffed the last pages of the Phenomenologyinto his pocket and took refuge in the house of a high official of the town. In the Phenomenology he attempts to understand the revolutionary terror of the Jacobins in terms of their interpretation of Freedom. Hegel celebrated Bastille Day throughout his life.

Having completed a course of study in philosophy and theology and having decided not to enter the ministry, Hegel became (1793) a private tutor in Berne, Switzerland. In about 1794, at the suggestion of his friend Hölderlin, Hegel began a study of Immanuel Kant and Johann Fichte but his first writings at this time were Life of Jesus and The Positivity of Christian Religion.

In 1796, Hegel wrote The First Programme for a System of German Idealism jointly with Schelling. This work included the line: “… the state is something purely mechanical – and there is no [spiritual] idea of a machine. Only what is an object of freedom may be called ‘Idea’. Therefore we must transcend the state! For every state must treat free men as cogs in a machine. And this is precisely what should not happen ; hence the state must perish”. In 1797, Hölderlin found Hegel a position in Frankfurt, but two years later his father died, leaving him enough to free him from tutoring.

In 1801, Hegel went to the University of Jena. Fichte had left Jena in 1799, and Schiller had left in 1793, but Schelling remained at Jena until 1803 and Schelling and Hegel collaborated during that time.

Hegel studied, wrote and lectured, although he did not receive a salary until the end of 1806, just before completing the first draft of The Phenomenology of Mind – the first work to present his own unique philosophical contribution – part of which was taken through the French lines by a courier to his friend Niethammer in Bamburg, Bavaria, before Jena was taken by Napoleon’s army and Hegel was forced to flee – the remaining pages in his pocket.

See Letter from Hegel to Niethammer, 13th October 1806.

Having exhausted the legacy left him by his father, Hegel became editor of the Catholic daily Bamberger Zeitung. He disliked journalism, however, and moved to Nuremberg, where he served for eight years as headmaster of a Gymnasium. He continued to work on the Phenomenology. Almost everything that Hegel was to develop systematically over the rest of his life is prefigured in the Phenomenology, but this book is far from systematic and extremely difficult to read. The Phenomenology attempts to present human history, with all its revolutions, wars and scientific discoveries, as an idealistic self-development of an objective Spirit or Mind.

During the Nuremberg years, Hegel met and married Marie von Tucher (1791-1855). They had three children – a daughter who died soon after birth, and two sons, Karl (1813-1901) and Immanuel (1814-91). Hegel had also fathered an illegitimate son, Ludwig, to the wife of his former landlord in Jena. Ludwig was born soon after Hegel had left Jena but eventually came to live with the Hegels, too.

While at Nuremberg, Hegel published over a period of several years The Science of Logic (1812, 1813, 1816). In 1816, Hegel accepted a professorship in philosophy at the University of Heidelberg. Soon after, he published in summary form a systematic statement of his entire philosophy entitled Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences which was first translated into English in 1959 and includes The Shorter Logic, as Part I. The Encyclopaedia was continually revised up till 1827, and the final version was published in 1830.

In 1818, Hegel was invited to teach at the University of Berlin, where he was to remain. He died in Berlin on November 14, 1831, during a cholera epidemic.

The last full-length work published by Hegel was The Philosophy of Right (1821), although several sets of his lecture notes, supplemented by students’ notes, were published after his death. Published lectures include The Philosophy of Fine Art (1835-38), Lectures on the History of Philosophy (1833-36), Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion (1832), and Lectures on the Philosophy of History (1837).

Hegel’s aim was to set forth a philosophical system so comprehensive that it would encompass the ideas of his predecessors and create a conceptual framework in terms of which both the past and future could be philosophically understood. Such an aim would require nothing short of a full account of reality itself. Thus, Hegel conceived the subject matter of philosophy to be reality as a whole. This reality, or the total developmental process of everything that is, he referred to as the Absolute, or Absolute Spirit. According to Hegel, the task of philosophy is to chart the development of Absolute Spirit. This involves (1) making clear the internal rational structure of the Absolute; (2) demonstrating the manner in which the Absolute manifests itself in nature and human history; and (3) explicating the teleological nature of the Absolute, that is, showing the end or purpose toward which the Absolute is directed.

Concerning the rational structure of the Absolute, Hegel, following the ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides, argued that “what is rational is real and what is real is rational.” This must be understood in terms of Hegel’s further claim that the Absolute must ultimately be regarded as pure Thought, or Spirit, or Mind, in the process of self-development. The logic that governs this developmental process is dialectic. The dialectical method involves the notion that movement, or process, or progress, is the result of the conflict of opposites. Traditionally, this dimension of Hegel’s thought has been analysed in terms of the categories of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Although Hegel tended to avoid these terms, they are helpful in understanding his concept of the dialectic. The thesis, then, might be an idea or a historical movement. Such an idea or movement contains within itself incompleteness that gives rise to opposition, or an antithesis, a conflicting idea or movement. As a result of the conflict a third point of view arises, a synthesis, which overcomes the conflict by reconciling at a higher level the truth contained in both the thesis and antithesis. This synthesis becomes a new thesis that generates another antithesis, giving rise to a new synthesis, and in such a fashion the process of intellectual or historical development is continually generated. Hegel thought that Absolute Spirit itself (which is to say, the sum total of reality) develops in this dialectical fashion toward an ultimate end or goal.

For Hegel, therefore, reality is understood as the Absolute unfolding dialectically in a process of self-development. As the Absolute undergoes this development, it manifests itself both in nature and in human history. Nature is Absolute Thought or Being objectifying itself in material form. Finite minds and human history are the process of the Absolute manifesting itself in that which is most kin to itself, namely, spirit or consciousness. In The Phenomenology of Mind Hegel traced the stages of this manifestation from the simplest level of consciousness, through self-consciousness, to the advent of reason.

The goal of the dialectical cosmic process can be most clearly understood at the level of reason. As finite reason progresses in understanding, the Absolute progresses toward full self-knowledge. Indeed, the Absolute comes to know itself through the human mind’s increased understanding of reality, or the Absolute. Hegel analysed this human progression in understanding in terms of three levels: art, religion, and philosophy. Art grasps the Absolute in material forms, interpreting the rational through the sensible forms of beauty. Art is conceptually superseded by religion, which grasps the Absolute by means of images and symbols. The highest religion for Hegel is Christianity, for in Christianity the truth that the Absolute manifests itself in the finite is symbolically reflected in the incarnation. Philosophy, however, is conceptually supreme, because it grasps the Absolute rationally. Once this has been achieved, the Absolute has arrived at full self-consciousness, and the cosmic drama reaches its end and goal. Only at this point did Hegel identify the Absolute with God. “God is God,” Hegel argued, “only in so far as he knows himself.”

In the process of analysing the nature of Absolute Spirit, Hegel made significant contributions in a variety of philosophical fields, including the philosophy of history and social ethics. With respect to history, his two key explanatory categories are reason and freedom. “The only Thought”, maintained Hegel, “which Philosophy brings … to the contemplation of History, is the simple conception of Reason; that Reason is the Sovereign of the world, that the history of the world, therefore, presents us with a rational process. “As a rational process, history is a record of the development of human freedom, for human history is a progression from less freedom to greater freedom.”

Hegel’s social and political views emerge most clearly in his discussion of morality and social ethics. At the level of morality, right and wrong is a matter of individual conscience. One must, however, move beyond this to the level of social ethics, for duty, according to Hegel, is not essentially the product of individual judgment. Individuals are complete only in the midst of social relationships; thus, the only context in which duty can truly exist is a social one. Hegel considered membership in the state one of the individual’s highest duties. Ideally, the state is the manifestation of the general will, which is the highest expression of the ethical spirit. Obedience to this general will is the act of a free and rational individual.

At the time of Hegel’s death, he was the most prominent philosopher in Germany. His views were widely taught, and his students were highly regarded. His followers soon divided into right-wing and left-wing Hegelians. Theologically and politically the right-wing Hegelians offered a conservative interpretation of his work. They emphasised the compatibility between Hegel’s philosophy and Christianity. Politically, they were orthodox. The left-wing Hegelians eventually moved to an atheistic position. In politics, many of them became revolutionaries. This historically important left-wing group included Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer, Friedrich Engels, and Karl Marx.

Bolshevik before the revolution. Met Trotsky in New York and the two were close until Bukharin joined Stalin’s struggle for power in 1923. Member of the ’Left-Communist’ faction which opposed signing of Brest-Litovsk Peace in 1917 in favour of a revolutionary war; Formed right bloc with Zinoviev, Kamenev and Stalin in 1923 against Trotsky, and was the major spokesperson for the turn to the rich peasants during the NEP. Remained with Stalin after Zinoviev and Kalinin joined the Left Opposition. Editor of Pravda 1918-1929. Head of Comintern 1926-1929. Broke with Stalin in 1928 to lead the Right Opposition. Trotsky remarked that Bukharin “must always attach himself to someone, becoming nothing more than a medium for someone else’s actions and speeches. You must always keep your eye on him.” His devotion to theoretical economics was tireless, and he was considered one of the principal theoreticians of the Bolshevik Party; authored a text book on Communism entitled The ABCs of Communism. Serge wrote, “His mind was effervescent, always alert and active, but rigorously disciplined. … a good-natured cynicism”. Expelled in 1929 from the party for his thoughts, he recanted soon afterwards. Executed after the Third Moscow Trial in 1938. (Under Gorbachev, Bukharin’s wife revealed that his confession was forced and published his hitherto secret rebuttal. There was an attempt to ’rehabilitate’ Bukharin at this time, seeking for a theoretical and historical justification for ’market socialism’).

Bolshevik before the revolution. Met Trotsky in New York and the two were close until Bukharin joined Stalin’s struggle for power in 1923. Member of the ’Left-Communist’ faction which opposed signing of Brest-Litovsk Peace in 1917 in favour of a revolutionary war; Formed right bloc with Zinoviev, Kamenev and Stalin in 1923 against Trotsky, and was the major spokesperson for the turn to the rich peasants during the NEP. Remained with Stalin after Zinoviev and Kalinin joined the Left Opposition. Editor of Pravda 1918-1929. Head of Comintern 1926-1929. Broke with Stalin in 1928 to lead the Right Opposition. Trotsky remarked that Bukharin “must always attach himself to someone, becoming nothing more than a medium for someone else’s actions and speeches. You must always keep your eye on him.” His devotion to theoretical economics was tireless, and he was considered one of the principal theoreticians of the Bolshevik Party; authored a text book on Communism entitled The ABCs of Communism. Serge wrote, “His mind was effervescent, always alert and active, but rigorously disciplined. … a good-natured cynicism”. Expelled in 1929 from the party for his thoughts, he recanted soon afterwards. Executed after the Third Moscow Trial in 1938. (Under Gorbachev, Bukharin’s wife revealed that his confession was forced and published his hitherto secret rebuttal. There was an attempt to ’rehabilitate’ Bukharin at this time, seeking for a theoretical and historical justification for ’market socialism’).

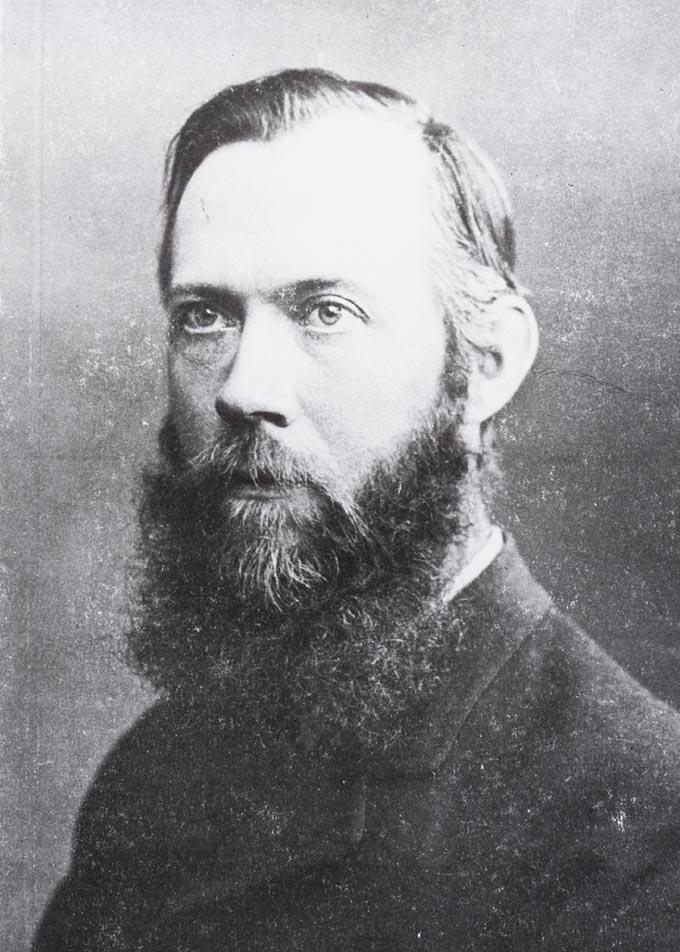

An entirely self-educated worker (his primary skill was as a tanner) who independently created dialectical materialism shortly after Marx & Engels. When he discovered the volumuous works of Marx and Engels, he become one of their most steadfast supporters.

Dietzgen’s main philosophical contributions to Marxism was the thorough an exposition of epistomology. He explained consciousness as an ideal product of matter (which he saw as eternally existing and moving, calling it the “universum”). He explained that natural and social being is the content of consciousness. Cognition, he went on, proceeds in sensory and abstract forms as a process of motion, from relative to absolute truth. This cognition he saw was an image of the world verified by that person’s experiences.

Dietzgen lived and worked in Germany, Russia, and the United States. He was strongly influenced by Feuerbach early on and was a militant atheist.

Hugo Dewar (1908-1980)

Hugo Dewar was born in 1908 in Leyton. Joining the Independent Labour Party in 1928, he subsequently co-founded, with F.A. Ridley, the Marxist  League. In 1931, he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain, to support their Balham group then battling against Stalinist policies, but was expelled in the following year. He took part in the founding of the Communist League, the first Trotskyist group in Britain, and continued to be active in Left Opposition groups until he was drafted into the army in 1943. On his discharge, he became a tutor in adult education, also writing many books and articles exposing Stalinism. He held firmly to his faith in revolutionary socialism until his death in June 1980.

League. In 1931, he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain, to support their Balham group then battling against Stalinist policies, but was expelled in the following year. He took part in the founding of the Communist League, the first Trotskyist group in Britain, and continued to be active in Left Opposition groups until he was drafted into the army in 1943. On his discharge, he became a tutor in adult education, also writing many books and articles exposing Stalinism. He held firmly to his faith in revolutionary socialism until his death in June 1980.

He published several pamphlets and three books: Assassins at Large (Wingate, 1951) – a full account of the executions outside Russia ordered by the GPU; and The Modern Inquisition (Wingate, 1953) – a history and an analysis of the ‘confession trials’ in the USSR and the People’s Democracies, and Communist politics in Britain: The CPGB from its origins to the Second World War.

Tony Cliff (1917-2000)

Born in Palestine to Zionist parents in 1917, Ygael Gluckstein became a Trotskyist during the 1930s and played a leading role in the attempt to forge a movement uniting Arab and Jewish workers. At the end of of the Second World war, seeing that the victory of the Zionists was more and more inevitable, he moved to Britain and adopted the pseudonym Tony Cliff.

In the late 1940s he developed the theory that Russia wasn’t a workers’ state but a form of bureaucratic state capitalism, a theory which has characterised the tendency with which he was associated for the remaining five decades of his life. Although he broke from “orthodox Trotskyism” after being bureaucratically excluded from the Fourth International in 1950, he always considered himself to be a Trotskyist although he was also open to other influences within the Marxist tradition.

His political legacy is embodied in the British Socialist Workers Party and its sister organisations in the International Socialist Tendency.

Marxist Humanist, born in the Ukraine in 1910 and moved with her parents to Chicago in 1920 to escape famine; expelled from the US Communist Party at age 14 as a Trotskyist; the first to decipher and translate Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts. Raya was a secretary to Trotsky for a time durng the 1930s, but she developed a position in opposition to Trotsky’s “statism”. She differs sharply also from “Marxist Humanists” like Fromm and Marcuse and from Lukacs, since from the beginning Raya took a clear stand against Stalinism. Raya was also the translator of Lenin’s Philosophical Notebooks, and these notes were an important part of her political position throughout her life. In her final years, she developed criticisms of Lenin over Lenin’s theory of the Party.

“ Ours is the age that can meet the challenge of the times when we work out so new a relationship of theory to practice that the proof of the unity is in the Subject’s own self-development. Philosophy and revolution will first then liberate the innate talents of men and women who will become whole. Whether or not we recognise that this is the task history has ‘assigned’, to our epoch, it is a task that remains to be done.” New Passions, 1973

Books

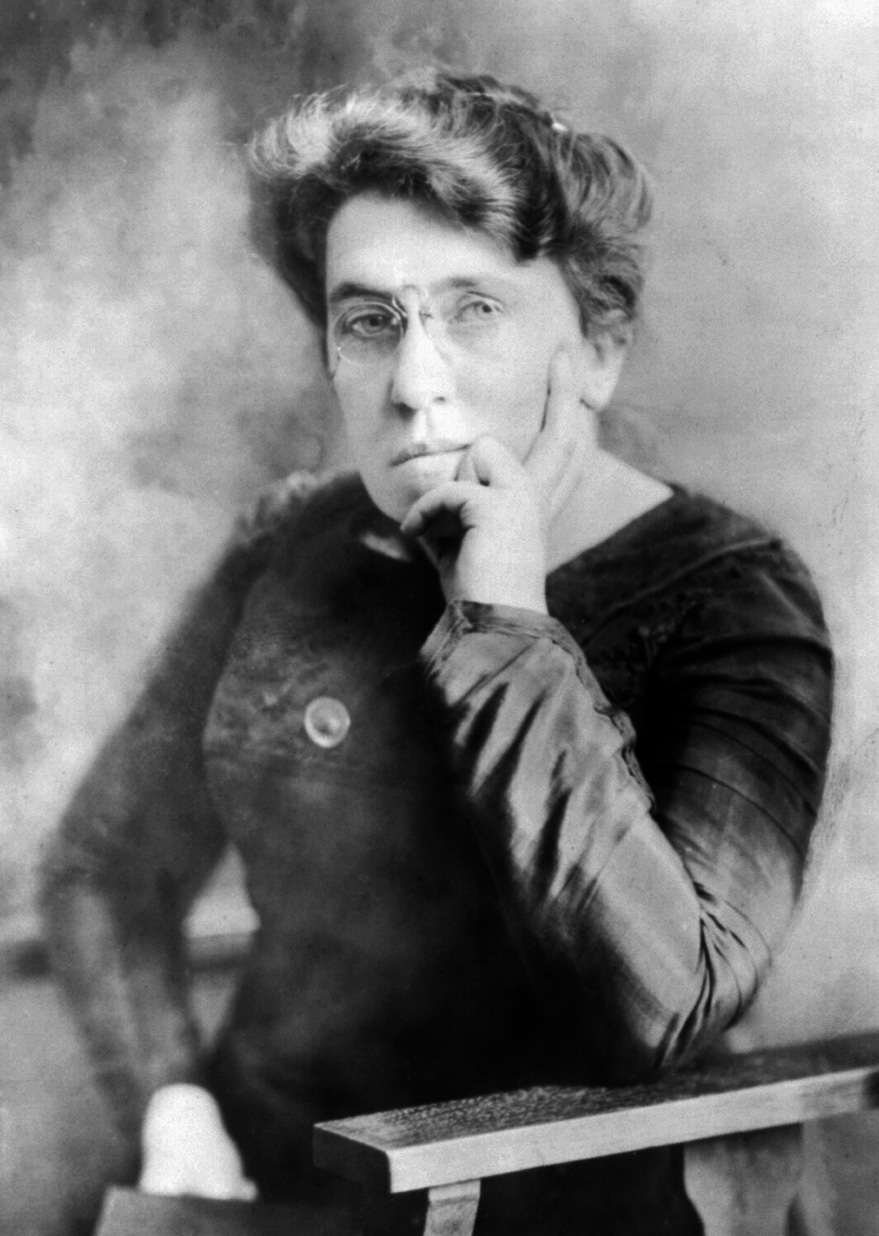

American anarchist, lecturer and writer in the United States and later a participant in the Spanish Civil War.

Born in Lithuania, her family owners of a small hotel, Goldman spent her early years in in Königsberg, East Prussia and later (in 1882) moved to St. Petersburg. As semi-wealthy Jews, Goldman and her family at times suffered from social and political persecution. By the time she was 16 (1885), in conflict with her father who tried to marry her off, she emigrated with her half-sister to the United States (Rochester, New York), where she began working in clothing factories. At 19, she was married for ten months, when she divorced her husband. Her two volume, 56 chapter autobiography Living My Life , begins three years after her arrival in the United States:

her off, she emigrated with her half-sister to the United States (Rochester, New York), where she began working in clothing factories. At 19, she was married for ten months, when she divorced her husband. Her two volume, 56 chapter autobiography Living My Life , begins three years after her arrival in the United States:

IT WAS THE 15TH OF AUGUST 1889, THE DAY OF MY ARRIVAL IN New York City. I was twenty years old. All that had happened in my life until that time was now left behind me, cast off like a worn-out garment. A new world was before me, strange and terrifying. But I had youth, good health, and a passionate ideal. Whatever the new held in store for me I was determined to meet unflinchingly.

After her move, she became close to Alexander Berkman, who together (in 1892) attempted to assassinate Henry Clay Frick, during the homestead steel strike. To raise money for buying the gun, Goldman unsuccessfully tried to prostitute herself. Their attempt of assassination was a failure, Frick was slightly injured, and workers were not at all incited to revolt. Berkman was sentenced to 22 years in prison, while Goldman attempted to defend Berkman with a passionately moral argument; her own involvement in the assassination was not tried.

By 1893, however, Goldman was imprisoned for her first time, after attempting to incite striking workers to revolt. Goldman was again imprisoned after distributing birth control literature. In 1906, Berkman was freed early from his prison term, and together they began again political education – founding Mother Earth, a periodical Goldman edited until it was forcibly suppressed by the U.S. government in 1917. In 1908 her naturalization as a U.S. citizen was revoked. Goldmann nevertheless stayed in the U.S., and continued to publicly speak on anarchism and also on the current European drama of Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg, George Bernard Shaw, and others.

In 1917, Goldman was imprisoned again (for two years) for setting up “No Conscription” leagues and speaking out against the US involvement in the war. In 1919, along with Berkman and 247 others, she was forcibly deported from United States to Soviet Russia as a subversive.

Here Goldman saw Russia for the first time under Soviet rule and strongly disapproved. She was horrified by the terrible living conditions in Russia and the repressive Soviet government. In the beginning she strongly spoke out against the government for its repressive measures against those who were attacking it during the Civil War. After the end of the (Western) Civil War, the nation in ruins by the destruction, Goldman chastised the government for the poor living conditions. When the Soviet government began encouraging the opposition parties, once brutally repressed, to help rebuild the nation, Goldman was outraged, believing that this was the ultimate compromise of revolutionary principles – to allow these “bourgeois” into the government. A few other anarchists joined Goldman in voicing extreme opposition to this, and attempted to start another Civil War. The first and last result of these attempts happened at Kronstadt, where mutinying soldiers attempted to lead a Civil War against the Soviet government. After this was brutally crushed by the Soviet government, Goldman, to disillusioned to continue to be revolutionary, left Soviet Russia for Western Europe.

In the last 20 years of her life she remained active through lecturing and writing. She later joined the antifascist cause in Spain during its Civil War and died working on its behalf.

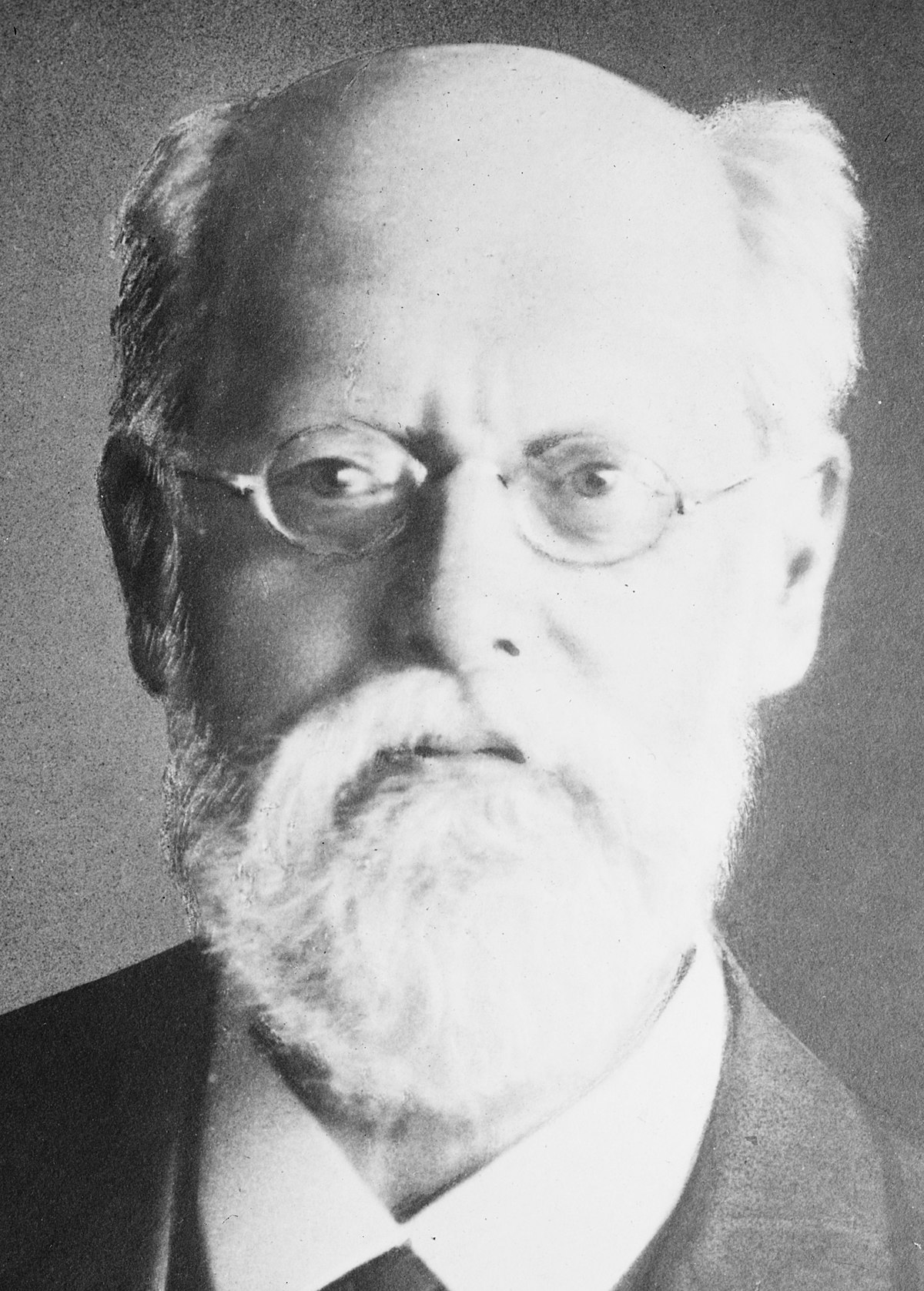

Karl Kautsky (16 October 1854-17 October 1938), was one of the best-known theoreticians of the Second International and until 1914 he was thought by many socialists to be the veritable “Pope of Marxism.”

Karl Kautsky was born in 1854 in Prague, the son of an Austrian mother and a Czech father. His father, Johann Kautsky, was a painter and his mother, Minna Jaich Kautsky, a novelist and actress whose novels were admired by Engels. The family moved to Vienna when he was seven years old and after the elite Vienna Gymnasium (Grammar School) he attended the University of Vienna in 1874, joining the Austrian Social Democratic party in 1875 and working as a journalist for them. In 1880 he joined a group of German socialists in Zurich who were supported financially by Karl Höchberg and who smuggled socialist material into the Reich at the time of the Anti-Socialist Laws. Influenced by Eduard Bernstein, Höchberg’s secretary, he became a Marxist and in 1881 visited Marx and Engels in England.

In 1883 he founded the monthly Die Neue Zeit in Stuttgart which became a weekly in 1890 and was its editor until 1917. The journal became immensely influential intellectually in socialist circles both in Germany and internationally. From 1885 to 1890 he worked with Engels in London and while there he published Karl Marx’ ökonomische Lehren, later translated in 1925 as The Economic Doctrines of Karl Marx which was probably the most widely read Marxist work on economics among SDP activists. It was so influential that long after Lenin had denounced him as a renegade it was still being used at the Moscow Lenin School in 1931 as by far the best treatment of the subject. Unfortunately his work on the French Revolution, Die Klassengegensätze von 1789(1889, 2nd ed. 1908), written at the same time, has never been translated into English.

He went back to Vienna in 1890 where he married his second wife Luise Ronsperger (1864-1944) who was later to die in Auschwitz and, after the repeal of the German Anti-Socialist Law, they went to live in Stuttgart. His draft of the SPD programme, approved by Engels, was accepted at the Erfurt Congress in 1891 and became another of his highly influential publications and at least three different translations into English were made of it. He started to develop a Socialist agrarian programme. His main work on this, The Agrarian Question, has only been recently translated (1998) and is still in copyright so not available here on the MIA. After the death of Engels, to whom he was closer than he had been to Marx, he wrote a warm tribute to him.

In 1896 he polemicised with Belfort Bax on the Marxist conception of history and in 1897 moved with his family to Berlin and in a series of articles in his paper called for participation of the SPD in the Prussian elections despite the disgracefully undemocratic constitution. The electoral process could be used a tribune to raise the consciousness of the workers and recruit them to socialism. In 1898 he took up the question of colonialism and the nationalities question in Austria. On colonialism he was one of the first Marxists to see its importance and to take an intransigent stand against it. When Bernstein attacked the traditional Marxist position in the later 1890s, later translated as Evolutionary Socialism (1908) Kautsky denounced him in articles and in an important book, Bernstein und das sozialdemokratische Programm, Stuttgart, 1899. Again there is no English translation of this very important work though there is a French one, Le Marxisme et son critique Bernstein. Kautsky correctly perceived that Bernstein’s emphasis on the ethical foundations of Socialism opened the road to a call for an alliance with the “progressive” bourgoisie and a non-class approach though in fact Bernstein’s approach to colonial questions would not strike many people today as excessively ethical. Kautsky thus appeared as the intellectual leader of the revolutionary left wing of the SPD though the growth of the Trade Union fraction was making the party more and more inclined to reformism. However it takes two to tango and the Imperial and Prussian governments showed not the slightest inclination to yield to democratic pressure from an opposition with the mildest of demands. In that situation it was possible for Kautsky to maintain his revolutionary credentials since there was little prospect of a viable reformist current in Wilhemine Germany. Above all Kautsky was opposed to non-working class alliances in the Imperial German situation.

In 1901 he handed over his ownership of Die Neue Zeit to the SPD while remaining editor. As an internationalist he opposed Socialist support for foreign tariffs and protection which he felt was at the expense of working class living standards. The SPD was less successful in influencing the Catholic than the Protestant working class and so he analysed the reactionary policies of the Catholic Church. In 1904 and 1905, under the influence of Russian events, Kautsky, although far more cautious than Rosa Luxemburg, argued against the SPD right wing that the whole question of the mass strike should be studied and not dismissed. However he never advocated such a mass strike in any specific situation – his demand that it should be considered as an option remained quite abstract though in theory he advocated a joint parliamentary and direct action approach in the Imperial German state to press for democratic reforms with the proviso that such action should have a good chance of success. At the Congress of the Second International at Stuttgart in 1907 he successfully attacked the pro-colonialist faction. The Foundations of Christianity was written in 1908. Der Weg zur Macht, (1909) translated as The Road To Power, and praised by Lenin, is sometimes thought to be his most “revolutionary” work. There is a poorer older version but an excellent new translation by Meyer (1996) exists which it is still in copyright and is available in many libraries.

Up to the outbreak of World War One, in addition to writing on themes already mentioned, he dealt with new questions such as anti-Semitism and inflation as well as articles on Finance Capital, Imperialism and national rivalries together with improved scholarly editions of Marx. His theories on imperialism, for over time his position changed, differed somewhat from that of Lenin. In particular he did not seem to believe that imperialism would drive to war, rather he saw it as a reactionary social phenomenon which appealed to the decaying class of the aristocracy and some marginal capitalist ones and was doomed. Only a fraction of the great mass of articles that he had written up to this point were translated into English and since many of the analyses were brilliant, even if he had much less to say on tactics, they deserve to be made available to a larger international audience as only through the medium of English can the largest number of people be reached today.

In 1914 the crisis struck and war was declared. At the meeting of the Reichstag caucus on 3 August 1914 which decided to vote for the war credits next day, Kautsky, not a member of the Reichstag himself, stated that the character of the war could not be determined, and therefore the right to defence of the fatherland had to apply to all countries involved in the war. He wanted the Party to demand from the government an assurance that it wanted no conquests, and if the government agreed the war credits should be approved, if not, not. This course of action was clearly utopian. He was utterly unprepared for the horror as he had increasingly tended to believe, as his pre-war theories of “Ultra Imperialism” suggest, that capitalism was sufficiently rational not to go to war. In June 1915, about ten months the war had began and when it had become obvious that this was going to be long sustained and appallingly costly struggle, he issued an appeal with Bernstein and Haase against the right and denounced the government’s annexationist aims. The SPD was dominated by its pro-war and Trade Union wing and tried to muzzle him so eventually Kautsky reluctantly split in 1917 and, together with Bernstein and Haase, joined the USPD as its right wing. In June 1917, after the first revolution in Russia he stated that this should lead to democracy but not to socialism since Russia was too undeveloped economically so Socialism would have to wait. In September 1917 the SPD dismissed him as editor of Die Neue Zeit. By this time he was becoming a more marginal figure as the “storm of the world” was crushing the SPD “centre” and strengthening the left of Luxemburg and Liebknecht. The collapse of the Imperial state in 1918 through military defeat and immense working class privation threw up a real revolutionary situation for which he was quite unprepared theoretically.

Soon after the Bolshevik revolution he denounced, in the The Dictatorship of the Proletariat (1918), all attempts to bring socialism forcibly to backward societies like Russia but he served as under-secretary of State in the Foreign Office in the short lived SPD-USPD government revolutionary government and worked at finding documents which proved the war guilt of Imperial Germany (Die Deutschen dokumente zum Kriegsausbruch …, 1919, The Guilt of Wilhelm Hohenzollern, also 1919). In response to Lenin’s accusations of being a renegade he wrote Terrorism and Communism in 1919.

After 1919 he became steadily less important. He visited Georgia in 1920 and wrote a book in 1921 on this Social Democratic country still independent of Soviet Russia and in 1920, when the USPD split, with a minority of that party he went back into the SPD. At the age of 70 he moved back to Vienna with his family in 1924 where he remained until 1938. In that period he continued his scholarship on the letters of Engels and his criticisms of Soviet Russia seeing that country as doomed by its inherent backwardness. He wrote something on Fascism after 1933 but he was also critical of the workers rising against Dollfuss in Vienna in 1934 but published his views anonymously and thus wrote about the Nazis in 1934 that “we should guard against overestimating the superiority of Hitler’s power” and that when capitalist democracy is threatened “we do not in any way regard ourselves as driven to the necessity of answering the destruction of democracy by an armed insurrection.”

In 1938 he fled to Czechoslovakia at the time of Hitler’s Anschluss, and thence by plane to Amsterdam where he died in the same year. His memoirs, on which he was working were only completed up to 1883 and were published posthumously in 1960.

“Ther e are people who assert that the Ministers are at fault. Not so. The country now realizes that the Ministers are but fleeting shadows. The country can clearly see who sends them here. To prevent a catastrophe the Tsar himself must be removed, by force if there is no other way.”

e are people who assert that the Ministers are at fault. Not so. The country now realizes that the Ministers are but fleeting shadows. The country can clearly see who sends them here. To prevent a catastrophe the Tsar himself must be removed, by force if there is no other way.”

Russian Social-Democrat from 1890s, active in international Socialist Women’s movement, and a member of the Mensheviks before 1914. Elected to Central Committee in 1917 and Commissar for Social Welfare in the Soviet government. With Bukharin in ‘Left Communist’ faction, opposed signing of Brest-Litovsk Peace (Lenin was for signing immediately, Trotsky for delaying in hope of a revolution in Germany, the WO advocated a revolutionary war against Germany); leader of the Workers Opposition. Sent to diplomatic posts in Mexico and Scandanavia. Sympathised with the Left Opposition, but subsequently ‘conformed’.

Central Committee in 1917 and Commissar for Social Welfare in the Soviet government. With Bukharin in ‘Left Communist’ faction, opposed signing of Brest-Litovsk Peace (Lenin was for signing immediately, Trotsky for delaying in hope of a revolution in Germany, the WO advocated a revolutionary war against Germany); leader of the Workers Opposition. Sent to diplomatic posts in Mexico and Scandanavia. Sympathised with the Left Opposition, but subsequently ‘conformed’.

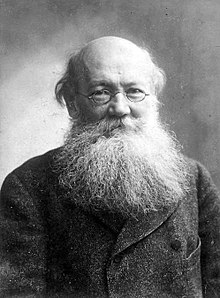

Py otr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian activist, revolutionary, scientist, geographer and philosopher who advocated anarcho-communism. Born into an aristocratic land-owning family, he attended a military school and later served as an officer in Siberia, where he participated in several geological expeditions.

otr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian activist, revolutionary, scientist, geographer and philosopher who advocated anarcho-communism. Born into an aristocratic land-owning family, he attended a military school and later served as an officer in Siberia, where he participated in several geological expeditions.

The son of a peasant farmer, Mao Tse-tung was born in the village of Shao Shan, Hunan province in China. At age 27, Mao attended the First Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in Shanghai, in July 1921. Two years later he was elected to the Central Committee of the party at the Third Congress.

From 1931 to 1934, Mao helped established the Chinese Soviet Republic in SE China, and was elected as the chairman.

Starting in October 1934, “The Long March” began – a retreat from the SE to NW China. In 1937, Japan opened a full war of aggression against China, which gave the Chinese Communist Party cause to unite with the nationalist forces of the Kuomintang. After defeating the Japanese, in an ensuing civil war the Communists defeated the Kuomintang, and established the People’s Republic of China, in October 1949.

Mao served as Chairman of the Chinese People’s Republic until after the failure of the Great Leap Forward, in 1959. Still chariman of the Communist Party, in May 1966 Mao initiated the Cultural Revolution with a directive denouncing “people like Khrushchev nestling beside us.” In August 1966, Mao wrote a big poster entitled “Bombard the Headquarters.”

Served as Party chairman until his death in 1976.

Originally a liberal journalist, Mehring joined the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) in the early 1890s. He rapidly became  acknowledged as an important theoretician. In the course of time he moved to the left and became associated with the current around Rosa Luxemburg. With the outbreak of World War I he was, despite his advanced years, a prominent member of the revolutionary opposition to the war along with Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and Clara Zetkin. He was a founder member of the German Communist Party established on New Years Day 1919, but died later in the month shortly after the murder of his comrades Luxemburg and Liebknecht.

acknowledged as an important theoretician. In the course of time he moved to the left and became associated with the current around Rosa Luxemburg. With the outbreak of World War I he was, despite his advanced years, a prominent member of the revolutionary opposition to the war along with Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and Clara Zetkin. He was a founder member of the German Communist Party established on New Years Day 1919, but died later in the month shortly after the murder of his comrades Luxemburg and Liebknecht.

Antonie Pannekoek was a Dutch astronomer, Marxist theorist, and social revolutionary. He was one of the main theorists of council communism.

“Marx stressed that it was the beginning of any science that constituted its real difficulty. This, together with Lenin’s emphasis upon the need to consider Hegel in connection with the first chapter of Capital, provides the starting point.” Introduction to Concepts of Capital

David Borisovich Goldendach. Born in Odessa, Ukraine, March 10, 1870. At 15, joined Narodnik revolutionaries. Arrested by Tsarist police, spent five years in prison. At age 19, made first trip to Russia Marxist circles abroad. When returning from second such trip in 1891, was again arrested at the border. After 15 months awaiting trial, was sentenced to four years solitary confinement and hard labor.

With the February Revolution of 1917, Riazanov returned to Russia. In August, he joined the Bolsheviks. In 1918, he began organizing Marxist archives. In 1920, Riazanov was made director of the new Marx-Engels Institute (which became the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute in 1931). Soon, Riazanov’s emissaries were out buying up whatever copies of Marx/Engels works and letters they could find. As Dirk Struik noted in a brief 1973 introduction to Riazanov: “By 1930, [the Institute] possessed hundreds of original documents, 55,000 pages of photostats, 32,000 pamphlets, and a library of 450,000 books and bound periodicals. Apart from the administrative offices, the archive, and the library, it had working rooms, a museum, and a publishing department.”

A contemporary of that time described Riazanov:

“The impression he left was one of immense, almost volcanic energy—his powerful build added to this impression—and tireless in collecting every scrap about, or pertaining to, Marx and Engels. His speeches at Party congresses, marked by great wit, often carried him in sheer enthusiasm beyond the bounds of logic. He did not hesitate to cross swords with anyone, not even with Lenin. He was treated for this reason with rather an amused respect, as a kind of caged lion, but one whose bark or growl usually had a grain of two of truth worth listening to.”

Riazanov’s Menshevik sympathies finally caught up with him in 1930, when he was relieved of duties and spent more time in prison. Kirov granted him permission to return to Leningrad, but after Kirov’s assassination, Riazanov had to return to Saratov, where he died in 1938.

John Silas “Jack” Reed was an American journalist, poet, and socialist activist, best remembered for Ten Days That Shook the World, his first-hand account of the Bolshevik Revolution. He married the writer and feminist Louise Bryant in 1916. Reed died of typhus in Russia in 1920

Born into a German Jewish middle class family in Berlin in 1889, he excelled at the Gymnasium before studying at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin with Otto Hirschfeld and Eduard Meyer. Soon, he established himself as an expert in Roman constitutional history. In 1914, Rosenberg proved to be a conformist representative of the German academy, believing in the “ideas of 1914,” and signing nationalist petitions. He then was drafted into the army, working for the Kriegspresseamt (the army’s public relations office).

After Germany’s defeat in 1918, he joined the new Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD), then on its formation in 1920, joining the KPD, the Communist Party of Germany. Rosenberg served on the Executive Committee of the Third International and as a member of the Central Committee of the German Communist Party. He was strongly influenced by Karl Korsch – later, like Korsch, describing Stalinist Russia as a ‘state capitalist’ society due to the Stalinist policy pursued as the basis of the First Five Year Plan. In 1927 he was expelled by the German Communist Party, withdrew from revolutionary politics, and became a democratic socialist. In 1931 he was finally made a Professor of History at Berlin University. When the Nazis came to power in 1933 he left for Switzerland, and then spent three years in exile in Britain from 1934-37 teaching at the University of Liverpool, before moving to United States, dying in New York in 1943 as a professor at Brooklyn College.

Born in Russia in 1886, I. I. Rubin was an activist, economics professor and then a researcher at the Marx-Engels Institute. In 1930 he was arrested, imprisoned, exiled and then disappeared. (For his sister’s account of this, see B.I. Rubina’s essay in R. A. Medvedev Let History Judge,translated from the Russian by Colleen Taylor, New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1972.) Rubin also authored four books. The English titles are: History of Economic Thought; Contemporary Economics in the West; Classics of Political Economy from the Seventeenth to the Mid-Nineteenth Century; and Essays on Marx’s Theory of Value. Summarized from “About the Author” in TOV.

Otto Rühle was a student of Alfred Adler and a German Marxist active in opposition to both the First and Second World Wars.

Otto Rühle and the German Labour Movement

Victor Lvovich Khibalchich (better known as Victor Serge) was born in Brussels, the son of Russian Narodnik exiles. Originally an anarchist, he joined the Russian Communist Party on arriving in Petrograd in February 1919 and worked for the newly founde d Communist International as a journalist, editor and translator. As a Comintern representative in Germany he helped prepare the aborted insurrection in the autumn of 1923.

d Communist International as a journalist, editor and translator. As a Comintern representative in Germany he helped prepare the aborted insurrection in the autumn of 1923.

In 1923 he also joined the Left Opposition. He was expelled from the party in 1928 and briefly imprisoned. At this time he turned to writing fiction, which was published mainly in France. In 1933 he was arrested and exiled. After an international campaign he was eventually deported from Russia in April 1936 on the eve of the Moscow Show Trials.

Upon arrival in the West he renewed contact with Trotsky but political differences developed and a bitter controversy developed between the two remaining veterans of the pre-Stalinist Russian Communist Party. Escaping from Paris in 1940 just ahead of the invading Nazi troops he found refuge in Mexico. During his last years Serge lived in isolation and died penniless shortly after the 30th anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution in November 1947.

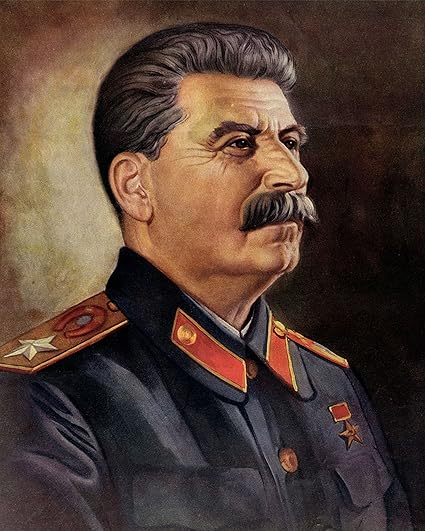

Stalin, a political name adopted when he was 34, meaning Man of Steel, studied for the priesthood under his real name, Dzhugashvili. Son of a shoe maker, he joined the Social Democratic party after being expelled from a theological school for insubordination. After the RSDLP split in 1903, Stalin  became a member of the Bolshevik party.

became a member of the Bolshevik party.

In Stalin’s early years he was continually in trouble with the local authorities. During this period he took the nickname Koba, after the famous Georgian outlaw and the name of a character in the romance “Nunu”, by the Georgian author Kazbek. The celebrated brigand Koba was known as a fighter for the the rights of the people, while the fictional Koba was depicted as sacrificing everything in his struggle against the Tsarist authorities on behalf of his people, but unsuccesful, freedom was lost.

Koba escaped prison exile several times, at his last escape he fled to St. Petersburg, where he became a member of the editorial staff of Pravda in 1912. Within a year, Stalin was arrested again and exiled to Siberia. He was released from exile by general amnesty after the February Revolution of 1917, and went back to the editorial staff of Pravda in Petrograd.

After the October Revolution Stalin was elected to the post of commissar for nationalities.

Throughout the following civil war, Stalin ascended the ranks of the government through extensive bureaucratic manoeuvering and in 1922, received the majority vote to become the General Secretary of the Communist party. In the same year Lenin called for his removal, explaining that Stalin had amassed to much power, in what was to become known as Lenin’s last testament.

Following Lenin’s death in 1924, a wave of reaction swept through the Soviet government. Stalin introduced his theory of socialism in one country, where he explained that Socialism could be achieved by a single country.

Unlike former inner-party debates, where the positions of either side were written in newspapers, talked about in public meetings and soviets; the reaction and practices of the long and devastating civil war, caused a ‘debate’ that was completely hidden from the public, in order to ‘establish the appearance’ of a healthy, stable, government.

In 1927, after years of bureaucratic manoeuvering, the members in the government that were part of the Left Opposition were deported on a wide scale. Immediately following, Stalin announced his theory of social fascism, describing that the theories of Social-Democracy and Fascism were essentially the same. Following this new theory, members of Social-Democratic organisations (of which Bolsheviks were once a part) were arrested or deported. In 1929 the right-wing of the Communist party, led by Bukharin, was removed from the so-called “soviet” government by the Stalinists.

In late 1928, Stalin introduced methods of productively advancing the Soviet Union via forced industrialisation and collectivisation. These efforts were tasked out in five year plans, the first of which included a widescale campaign of mass executions, arrests, and deportations of the kulak class.

Russia advanced tremendously from the draconian measures implemented to ensure that “socialism in one country” could survive. Russia moved from complete devastation and destruction after WWI and the Civil War, to become a nation that was one of the most powerful in the world: achieving such goals that 30 years previous would have been viewed as wholly impossible.

From 1934 to 1939 Stalin ordered a series of executions and imprisonments, largely directed towards people within the Soviet government. Half of the members of the first Council of Peoples Commissars were executed in 1938 (A quarter of them had died natural deaths before hand, of the remaining quarter only Stalin lived past 1942). Some government officials executed were thought to be Nazi agents or sympathisers, while others were accused for planning to overthrow the Soviet government. Members of the Left Opposition who were allowed to return to the party after accepting Stalinism were soon executed, those who remained abroad were hunted down and killed. Also executed were people belonging to the right-wing of the party (Bukharin and others). The exact number of people executed is not known, estimates range from thousands to millions.

During WWII Stalin organised and lead the Soviet Union to victory over the invading Nazi armies.

Boris Souvarine, also known as Varine, was a French Marxist, communist activist, essayist, and journalist. Souvarine was a founding member of the French Communist Party and is noted for being the only non-Russian communist to have been a member of the Comintern for three years in succession.

August Thalheimer (1884-1948) was a member of the German Social Democratic Party before the First World War, and editor of one of its papers, the Volksfreund. From 1916 he assisted in the production of the Spartakusbriefe, was a member of the USPD (Independent Socialists ) from 1917, and a founder member of the German Communist Party (KPD). He quickly rose to prominence as the party’s main theoretician, being editor of Rote Fahne as well as of Franz Mehring’s manuscripts left unpublished at his death.

) from 1917, and a founder member of the German Communist Party (KPD). He quickly rose to prominence as the party’s main theoretician, being editor of Rote Fahne as well as of Franz Mehring’s manuscripts left unpublished at his death.

During the 1923 crisis he was Minister of Finance in the Württemburg local government, was subsequently blamed along with Brandler for the debâcle, and was called to Moscow in 1924, where he worked in the Communist International apparat, as well as for the Marx-Engels Institute. His lectures delivered at the Sun Yat-Sen University in 1927 were published as a textbook in philosophy (which appeared in English as Introduction to Dialectical Materialism, New York, 1936), and he also worked on the draft programme of the Comintern along with Bukharin. Pressure from the KPD, still uneasy with the leadership of Thälmann, secured his return to Germany in 1928, but a year later he was expelled from the KPD along with Brandler, and they went on to form the KPO, or Brandlerites.

The Brandlerite organisation restricted most of its criticisms to the foreign policy of the Soviet Union, whilst maintaining that its domestic operations were basically healthy. Thalheimer insisted that: ‘We do not want to draw the conclusion that as the politics of the Comintern are wrong, it must follow that the politics of Russia are also wrong.’ (GdST, 4/1931) Thalheimer himself supported forced collectivisation and Stakhanovism, and whilst in Barcelona became involved in a heated argument with Nin over the POUM’s condemnation of the first Moscow Trial.

In exile in Paris from 1932 onwards, Thalheimer went to Spain in 1936, and then back to France again where the KPO’s exile organisation worked. When six members of the KPO were arrested in Barcelona by the Stalinists and charged with the usual crimes in July 1937, he issued a statement co-signed by Brandler saying that:

‘We take upon ourselves any political and personal guarantee for our arrested comrades. They are anti-Fascists and revolutionaries, incapable of any action that could be construed as high treason to the Spanish Revolution.’

They were not to stay long in Paris. In 1940 France fell to Hitler, and Thalheimer fled to Cuba, where he died in 1948.

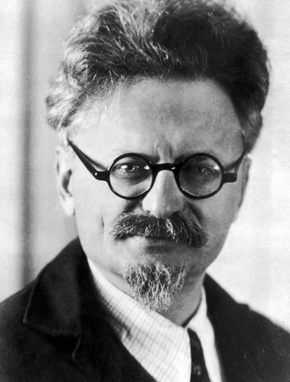

Trotsky was a key figure in the Bolshevik seizure of power in Russia, second only to Vladimir Lenin in the early stages of Soviet communist rule. But he lost out to Joseph Stalin in the power struggle that followed Lenin’s death, and was assassinated while in exile.

Trotsky was born Lev Davidovich Bronstein on 7 November 1879 in Yanovka, Ukraine, then part of Russia. His father was a prosperous Jewish farmer. Trotsky became involved in underground activities as a teenager. He was soon arrested, jailed and exiled to Siberia where he joined the Social Democratic Party. Eventually, he escaped Siberia and spent the majority of the next 15 years abroad, including a spell in London.

In 1903, the Social Democrats split. While Lenin assumed leadership of the ‘Bolshevik’ (majority) faction, Trotsky became a member of the ‘Menshevik’ (minority) faction and developed his theory of ‘permanent revolution’. After the outbreak of revolution in Petrograd in February 1917, he made his way back to Russia. Despite previous disagreements with Lenin, Trotsky joined the Bolsheviks and played a decisive role in the communist take-over of power in the same year. His first post in the new government was as foreign commissar, where he found himself negotiating peace terms with Germany. He was then made war commissar and in this capacity, built up the Red Army which prevailed against the White Russian forces in the civil war. Thus Trotsky played a crucial role in keeping the Bolshevik regime alive. He saw himself as Lenin’s heir-apparent, but his intellectual arrogance made him few friends, and his Jewish heritage may also have worked against him. When Lenin fell ill and died, Trotsky was easily outmanoeuvred by Stalin. In 1927, he was thrown out of the party. Internal and then foreign exile followed, but Trotsky continued to write and to criticise Stalin.

Trotsky settled in Mexico in 1936. On 20 August 1940, an assassin called Ramon Mercader, acting on Stalin’s orders, stabbed Trotsky with an ice pick, fatally wounding him. He died the next day.

Born November 29, 1856; died May 17, 1918. One of the founders of the first Marxist organisation in Russia: the Emancipation of Labour group, Plekhanov had at one time been a member of the Peoples Will party. After the dissolution of the Emancipation of Labour group, Plekhanov later joined the Russian Social-Democratic party, becomming a Menshevik after the split in the party.

Plekhanov studied in the St. Petersburg Konstantinovskoe Military school, but later transfered to the Mining Institute. While attending university Plekhanov became involved with Narodnaia Volia, the People’s Will revolutionary party. After his second year in school, Plekhanov dropped out to devote himself entirely to revolutionary work. Despite the Narodnaia Volia’s aim towards the emancipation of the peasantry, Plekhanov focused on organising the emerging Russian proletariat; Plekhanov understood, with the help of the writings of Marx and Engels, that only through the proletariat could Socialism be achieved.

Plekhanov studied in the St. Petersburg Konstantinovskoe Military school, but later transfered to the Mining Institute. While attending university Plekhanov became involved with Narodnaia Volia, the People’s Will revolutionary party. After his second year in school, Plekhanov dropped out to devote himself entirely to revolutionary work. Despite the Narodnaia Volia’s aim towards the emancipation of the peasantry, Plekhanov focused on organising the emerging Russian proletariat; Plekhanov understood, with the help of the writings of Marx and Engels, that only through the proletariat could Socialism be achieved.

The political differences between Plekhanov and the People’s Will group, in addition to its adoptation of terrorism after several failed attempts to rally the peasantry to revolution, caused Plekhanov to split off from the group and form a smaller group continuing the old methodolgy of going to the people and agitating. By 1880, hounded by the Tsarist Okhanara, Plekhanov fled Russia, not returning until the General Amnesty granted by the Provisional Government, in 1917.

In 1882, while in exile, Plekhanov rendered a Russian translation of the Manifesto of the Communist Party, with a preface written by Marx and Engels, replacing the first translation that had been made in 1869 by the anarchist Bakunin, which had translation flaws. In 1883 Plekhanov helped form the first Russian Marxist organisation: the Emancipation of Labour group. Plekhanov renewed his struggle against Narodism, pointing out flaws in revolutionary appeals to the Russian peasantry alone, and flaws in the tactics of terrorism, being the opposite of mass action; a requirment for Socialist revolution.

Throughout the 1890s the influence of the Emancipation of Labour group on Russia’s proletariat, through smuggling pamphlets into the country, built up a revolutionary following within Russia, enabling the party to be engaged in labour and union struggles in Russia. This upsurge of labour union activity, guided by the principles of Marxism which had been translated and distributed into Russia by the Emancipation of Labour group, gave rise to the Russian Social-Democratic Party, in 1898. The unity of this party Plekhanov would spend the rest of his life defending, save for when the Soviet Government was established, when he disavowed the left half of the party: the Bolsheviks.

In the late 1800s, one of Plekhanov’s most passionate supporters was Vladimir Lenin. Lenin admired Plekhanov as the founder of Russian Marxism and strove to master the revolutionary activity and party building Plekhanov had begun. In 1900, when Lenin founded Iskra, Plekhanov wrote for the paper, and together, they supported proletarian revolution backed by Marxist theory while attacking revisionists such as Eduard Bernstein.

By the time of the split in the R.S.D.L.P., Lenin and Plekhanov came head to head, never to theoretically meet again. Plekhanov wrote a book entitled, What is not to be Done, explaining that the party should not split, that, “rather than having a split, it is better to put a bullet in one’s brain”. Lenin, on the other hand, emphasised the importance of a split, in order to develop the different trends and opinions in the revolutionary movement. The party did split during the Second Congress, forming the Bolshevik and Menshevik parties; of which Plekhanov ultimately sided with the Mensheviks.

Plekhanov theoretical position was that Russia’s proletariat should be sent to the battlefields against the Russian autocracy, and after having overthrown it, they should work to establish a bourgeois government. This would allow the proletariat to grow to a great size, while so too did the bourgeoisie, allowing a bigger proletariat class to overthrow the now more powerful bourgeoisie, believing that the proletariat would eventually overpower the bourgeois government. Plekhanov stressed that Russia must pass through genuine capitalistic development, in order for the conditions and tools to be built to enable a Socialist revolution to occur.

During the Russian Revolution of 1905, Plekhanov’s theories were shown to be incorrect in many respects, most prominently in his negligence towards the revolutionary strength of Russia’s peasantry. Instead of revising his theories in accord with the new developments of history, Plekhanov stuck to them and defended them admist a now much larger chorus of attackers: his theories were rapidly being discarded into the dustbin of history.