The following was adapted from a talk given at the online CPUSA Marxist School in 2022.

The Black Lives Matter uprising of 2020 was a powerful demonstration of unity among a wide strata of people marching in cities and small towns against police oppression. It was led mostly by African American youth, who, like their forebears in the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, showed the importance of their role in working-class and democratic movements. Therefore, it is vital to concretize the primary forces that African American youth are struggling against.

When we talk about “right-wing forces,” we are speaking specifically about a sector of finance capital whose agenda is to further exploitation of workers at all costs. The lead implementers of this agenda don’t care about preserving social peace, the bounds of law, any sort of democratic considerations, or even life. For them, the maximization of profits stands as the sole end, regardless of the means used to split the working class to achieve it, whether by racism, sexism, nationalism, chauvinism, homophobia, transphobia, or anticommunism. Unfortunately, many of our fellow workers mistake their own interests for this agenda.

It is these forces, embodied by the Republican Party in coalition with conservative think tanks, lobbying firms, and corporate backers, that African American youth find themselves struggling against. We’ll take a look at the many-sided features of this right-wing agenda and attempt to sketch a plan of continued resistance and pushback.

Unemployment

We can begin by looking at the unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-old African American men and women against the unemployment rate for men and women of all races.

Men

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate for Black men aged 16–24 has consistently been higher than the average across all races for the same age group and sex since January 2020. The rate peaks at 29.3% in June 2020 while the average rate lies eight and a half percentage points lower at 20.9%.

Women

The same holds true for Black women in the 16–24 age group compared with all races of women in the same age category. At their peak unemployment rate in May 2020, 31.7% Black women were unemployed vs. 26.5% of women in general.

Why?

The data provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ 2019 Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey reveals a telling pattern. After filtering the data to see only those occupations where either African Americans or women are overrepresented, it becomes clear that in the majority of occupations where Black people are overrepresented (83 out of 139), women are also overrepresented; for roughly half of the occupations where women are overrepresented (83 out of 173), Black people are overrepresented.

Most of these jobs are healthcare, service and retail, packaging, childcare and early education jobs. This puts African Americans of all ages—but especially youth—at the front lines during the early days of the pandemic. Some of the lines of work mentioned above are also those that are most likely to employ youth, and the special measures taken in early to mid-2020 to protect either people or profits caused those jobs where young workers are concentrated to disappear.

However, this is only a small piece of the whole picture. For one, the numbers cited above do not include workers marginally attached to or not in the labor force. African American youth also have to deal with mass incarceration and criminalization, to be covered later, which can lock us away and label us as de facto unemployable for years. Also, the incarcerated are not even counted among the unemployed. In addition, concerted efforts to keep African American youth undereducated and out of jobs that tend to be somewhat more resilient to job market crashes continue.

Education

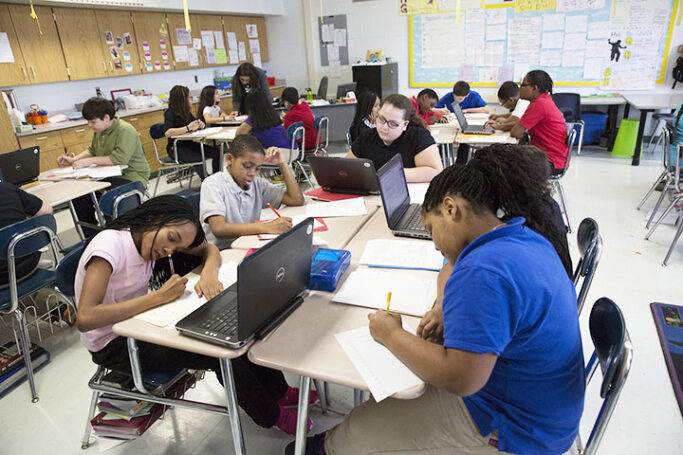

With so many roadblocks placed in the way, “getting an education” is no easy feat for African American youth. To start, though preschool enrollment among Black children aged 3–5 is comparable to that of other ethnic groups at a rate of 54.5%, a difference in quality may limit the benefits of enrollment when compared to outcomes for children of other races. Indeed, the gap in school readiness between white and Black students in terms of math, reading, and behavior has not improved at the same rate as the gap between white and Hispanic students or rich and poor students. In fact, the rate of gap closure between white and Black students is not statistically distinguishable from zero!

In kindergarten, the math-preparedness gap widens between white and Black students. This suggests that experience in early education is dependent on the race of the student, and this suggestion is borne out by tracking educational experience throughout students’ lives.

According to a study in the Economics of Education Review, non-Black teachers were found to have lower expectations than Black teachers for the same Black students. Whether this is because non-Black teachers are overly pessimistic or Black teachers are overly optimistic was unclear in this study. However, what is clear is that students pick up on these differences in expectations, and so their educational outcomes tend to be negatively affected.

As students move into higher education, the gap begins to yawn. By the time students have reached middle school, disparities in access to advanced courses grow into disparities in high school completion rates, college enrollment rates, quality of colleges attended (in terms of alumni earnings), and college graduation rates.

All the while, aforementioned right-wing forces have been allowed to whitewash the racist history of the United States and anti-racist struggle from many states’ school curricula. They have also successfully resisted the portion of the Build Back Better bill which would have provided funding to historically Black colleges and universities. Supporters have been forced to fight for the piece-by-piece passing of the rest.

Health

We are still in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. When it comes to the government and private-sector response to the pandemic, the preexisting inequities in the communities in which African Americans live have amplified COVID-19’s destruction in these communities.

For example, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, one of the nation’s many HBCUs, has well under 1,000 students and is critically underfunded as a public university. As a result, the university had to make a decision regarding students’ housing that was a loss either way: remain open without all the necessary COVID precautions, or close student housing and lose many potential students due to lack of readily accessible public transportation or internet access at home.

This situation is far from unique. Many HBCUs and K–12 school districts across the country were forced to make similar decisions. Within African American communities, there remains a scarcity of access to preventative and palliative measures against COVID-19, including masks, testing kits, and vaccines.

With all the pressures put on African American youth, one must also consider patterns of mental health. The Congressional Black Caucus put together the Emergency Taskforce on Black Youth Suicide and Mental Health in April 2019 that addressed these issues for Black youth between the ages of 5 and 17.

A myth is often propagated that Black youth are not susceptible to suicide, but the research gathered by this taskforce shows that suicide rates among Black youth are increasing faster than for any other racial or ethnic group. Though the precise causes of this outsized rate of increase are as yet unknown, the pressures discussed in this article are no doubt deeply linked.

The HIV/AIDS pandemic also continues to disproportionately affect Black youth. Black people make up only 13% of the population but 42% of new HIV cases, most of which are occurring among young gay Black men, followed by young Black women. A major reason for this is lack of access to the same health care resources as others. The infected are less likely to know they are HIV-positive and less likely to receive antiretroviral therapy, which can keep patients healthy and even lower viral loads to the point that sexual transmission is impossible.

How does one access these resources? If not provided by a local branch of government or other non-profit agency or advocacy group, access is locked behind employment benefits. Access to health is often dependent on access to jobs, and with higher than average rates of unemployment, observed health outcomes are not surprising.

Socioeconomic status is tied to many health indicators—not just COVID and HIV rates. The medications needed to prevent and treat illness are too often not publicly funded, not regulated, or distributed without sufficient information about how to use various treatments safely in conjunction with other pharmaceuticals. This further restricts healthcare to those with the resources to obtain personalized medical care and guidance.

Not only this, but reproductive health is under attack. With Roe v. Wade overturned, abortion rights have already been stripped away for one in three women.

This is a multidimensional health issue, affecting the physical, mental, and community well-being of the entire U.S. working class. The task of raising the next generation of workers often falls to women, whether through unpaid labor not recorded in labor statistics or the recorded labor of workers in the pediatric care, domestic, and related industries. The Black community is no exception. All rights built on top of the Roe v. Wade ruling in particular are crumbling, and other privacy, personal, and bodily autonomy rights are also imperiled.

Sexuality & Gender

Half of Black people are women (a fact worth explicitly reiterating at times!), and 1 in 20 Black people are LGBTQ, with a greater proportion in young populations.

Black women are at the intersection of two great oppressive forces: racism and sexism. Not only is there a wage gap between Black women and non-Hispanic white men (65 cents to the white male dollar), but also between Black and white women (65 vs. 81 cents to the white male dollar, respectively).

Black women also suffer from higher pregnancy-related mortality rates than other races, and at a rate 2–3 times higher than white women. 20–40 Black women die per 100,000 live births for women under 20 to 30 years old, and only increasing with age. Pregnancy-related death rates are similar for American Indian and Alaskan Native women. With the overthrow of Roe v. Wade, this adds up to a de facto death sentence for Black women, who are more likely both to perish as a result of pregnancy and to need abortion services.

This is no coincidence. Birth rates are below what is necessary for replacement of the labor force based on the statistical replacement rate of 2,100 births per 1,000 women. In 2020, the U.S. total fertility rate fell to 1,637.5 births per 1,000 women. Partially as a result of this, the ruling class has launched an open assault on reproductive rights across the country.

Black transgender people are also under attack. They have a 26% unemployment rate, “two times the rate of the overall transgender sample and four times the rate of the general population.” Homelessness stands at an absurd 41%, “more than five times the rate of the general U.S. population.” They live in extreme poverty, with 34% reporting less than $10,000 per year as their household income. This is more than twice the 15% rate for transgender people of all races, almost four times the 9% rate in the general Black population rate, and more than eight times the 4% rate in the general U.S. population. They are also being devastated by HIV rates,, with a 20.23% incidence rate vs. 2.64% for transgender people of all races, 2.4% for the general Black population, and 0.6% of the U.S. population overall.

Ultimately, we have to understand the racialized sexism that Black women and the Black queer community in general face if we are to properly struggle against patriarchy and for transgender liberation. We have to act in solidarity with these vulnerable groups that are often ignored.

Mass Incarceration & Police Brutality

Mass incarceration is also a major issue facing Black youth, who are more likely to be incarcerated than their white peers in every state. In general, Black adolescents are 4.4 times more likely to be arrested than youth of other races. This is a manifestation of the well-documented school-to-prison pipeline. Once entered in the pipeline, Black people of all ages face differential treatment in the American justice system, including higher arrest rates, higher bail, and longer sentences on average. To advance working-class and democratic struggles, it is imperative to embed ourselves in mass movements like Black Lives Matter, which are at the forefront of the struggle against mass incarceration.

Inner-City Violence

To mention mass incarceration without mentioning inner-city violence would be a mistake. The two phenomena are intimately tied. Black youth are at a higher risk of facing or witnessing physical violence at a very young age. This exposure has a dramatically negative, traumatizing affect on the developing Black child. It is also one of the main psychological drivers behind continued gang violence, which Black youth are overwhelmingly the victims of.

For Black teenagers, the homicide rate is more than six times greater than their white peers and three times the rate of all races in general.

The issue of gang violence is complicated and related to the global system of anti-Black oppression. It is often tackled in ways which fundamentally misunderstand and stereotype Black children.

As with mass incarceration, socialists need to support current Stop the Violence movements across various urban centers. The issue goes beyond explicit movements against violence—it is also largely about community stability. We need to support struggles for nutritional food sources, well-funded schools, functioning roads, hospitals, libraries, youth centers, and other vital resources in Black communities.

How do we fight back and win?

What actions can we take to assist in the struggles that Black youth face? Given our capacities and the wide range of struggles we must support, it is best to find and work with organizations already leading this fight. These include Black Youth Project, the I Project, Equal Justice Initiative, Black Lives Matter, National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, and National Black Justice Coalition.

We also need to host our own events focused on Black liberation. We can have our own Stop the Violence rallies, Black youth fundraisers, awareness campaigns for gendered violence, school and food drives, and other initiatives. And we need to continue our drive to recruit to the Party, and we need to recruit Black youth into the Young Communist League.

As Henry Winston, the beloved former chair of the Communist Party, iterated in his classic work Strategy for a Black Agenda, Black workers are triply oppressed—they are under the threat of fascism, racism, and super-exploitation in the workplace. This was true in 1972, and it is even more true now.

We need to give special priority to issues faced by Black youth, and work to advance the leadership of Black young people in our march toward advanced democracy and socialism. Black youth make up a significant part of our working class and people leading the fightback, and it is our obligation to struggle for total liberation of all peoples. Despite the oppression they have faced, Black youth are at the center of the future Communist movement!